There’s a good reason why many people’s go-to fat is olive oil, with its gorgeous hue and romantic Mediterranean origin story. But what if there was another fat option that’s equally handsome and even more multipurpose? In fact, though animal fats have fallen out of fashion as food items for a time as campaigns against saturated fat loomed large, the reality is different — and pork fat is not only an acceptable option, but an optimal one in many cooking applications.

Pork fat is a tasty and economical cooking fat with numerous culinary uses. To get the skinny on all things pork fat, we turned to McCullough Kelly-Willis, founder of Chicago Meat Collective. Chicago Meat Collective is a hands-on meat school educating the Chicago community on nose-to-tail butchery. Kelly-Willis is an advocate for local, humanely-raised meat. Her collective buys whole animals directly from local farms to break down in a classroom setting (spoiler alert: this is the first step in sourcing high-quality fat), and we’d imagine breaking down whole animals results in lots of extraneous fat.

We spoke with Kelly-Willis about the various culinary options available to utilize this “cut” of the animal. Here are some genius ways to use pork fat in your next meal.

Be sure to use the correct type of pork fat

According to McCullough Kelly-Willis, pigs produce several different types of fat, with two types used for culinary application: pork fatback and lard (which differs from suet). Though both can be useful when cooking, each type of pork fat is different enough that you’ll want to utilize the correct one depending on the dish you’re preparing.

Pork fatback, for instance, is harder in texture because it’s found directly under the skin of the pig’s back and travels from the upper neck down to the animal’s hips. Given the fat’s solid texture, it’s best for applications where the fat should remain cold and intact. Kelly-Willis suggests using fatback with ground meat-type recipes, such as sausages, meatballs, terrines, and other forcemeats (more on that later.)

Lard is the other common pork fat — and perhaps the more recognizable option, too. Lard is “rendered and strained fat that is sold in a tub or a jar,” Kelly-Willis explained, and is “solid but giving at room temperature.” The texture is similar to tallow or coconut oil. Because lard is soft and spreadable when tempered, it’s excellent for applications that require it to be melted. “This is the best fat for frying, making confit, and soap making,” Kelly-Willis added.

Purchase pork fat from high-quality, pasture-raised pigs

As noted in the previous slide, not all pork fat is equal in terms of flavor, performance, or nutrition. To source pork fat that’s both tasty and nutritious, then, look to how the animal was reared. After all, it likely won’t come as a shock that healthy, humanely-raised pigs produce higher-quality fat.

“Fat can be very nutritious when it comes from animals with ample access to sun, dirt, and the ability to express their natural behaviors,” McCullough Kelly-Willis told Look. This is because a pig’s biology is impacted by its environment — just like humans. Pigs that are free to roam outdoors, for example, are apt to absorb more vitamin D from the sun that’s then stored in their fat. In fact, lard from pasture-raised pigs is a substantial food source of vitamin D. Lard also contains less saturated fat and cholesterol than butter (not that butter is bad; we love butter, after all), and, unlike shortening, contains no trans fat.

Farmer’s markets and whole-animal butcher shops are excellent resources for finding high-quality pork fat. Even if it does not appear for sale, many shops — especially those that break down whole animals in-house — will sell you some if you ask nicely. When purchasing, look for the right color and scent. Kelly-Willis suggests purchasing pork fat that’s “white or yellowish and has a relatively neutral scent.”

Use in place of vegetable oil when deep frying

Vegetable oil is lauded for its low cost, high smoke point, and neutral flavor profile, which makes it a great choice when deep frying. Lard, however, performs similarly when melted because its smoke point — the temperature it reaches before, well, smoking — is only slightly lower than that of vegetable oil at around 375 degrees Fahrenheit, as McCullough Kelly-Willis explained. Using a fat with a high smoke point is essential when deep frying to prevent burning (which compromises the fat’s nutrition and gives foods a bitter, acrid flavor). Hence, lard has excellent frying potential.

Kelly-Willis recommends using lard to cook fried chicken via a double-fry method. Start by cooking the chicken at 325 degrees Fahrenheit until it’s cooked through, “then drain and rest for about 10 minutes while you bring the lard up to 350 for a final, quicker fry to get crunch and color.”

Additionally, lard can be cooled and reused for later dishes — as long as you strain any food debris from the pork fat before storing it to prevent spoilage. You can even use the same batch of lard multiple times for frying, though the quality will degrade over time.

Grind into sausage or meatballs

Dianahirsch/Getty Images

There are many recipes for homemade sausage that contain pork fat, but the type of pork fat you choose is key. McCullough Kelly-Willis suggests using fatback when making sausage or grinding meat at home for meatballs, meatloaves, and terrines. Fatback is solid but still supple, so it holds up to the heat and friction of a meat grinder without disintegrating, giving your sausage a juicy, rather than crumbly, final texture.

“Lean meats like chicken and turkey benefit from pork fatback if you want to create a juicy sausage,” Kelly-Willis told us. Whether you’re making smash burgers, regular burgers, or chicken meatballs, the benefit of grinding meat is that you get to control how lean or fatty the meat mixture is, depending on your preference, diet, or the protein you choose. “Aim for about 10-20% fat in the mix for meatballs, meatloaf, or a meat sauce like bolognese, and closer to 30% for sausage and terrines.”

When grinding your own meat, all equipment and ingredients must stay bone-chillingly cold (37 degrees Fahrenheit or below) to ensure the proper texture. Additionally, avoid using lard in these recipes, as it won’t function the same as fatback when incorporated into ground meat mixtures.

Make carnitas with pork fat

Carnitas – the much-loved taco filling hailing from the Michoacan region of Mexico — is a meaty, slow-cooked treat. The secret to that succulent, melt-in-your-mouth texture is fat — more specifically, lard. In traditional carnitas recipes, the pork gets cooked in large quantities of lard, similar to deep frying but without the high heat.

“Tough cuts of pork plus pork lard and a bit of salt are all it takes to make satisfying carnitas,” McCullough Kelly-Willis told Look. Start by seasoning the meat with salt and spices, or marinade it for a few hours with other aromatic ingredients. After the meat marinates, add it to a Dutch oven and cover the mixture with lard. Cook the meat at a gentle simmer until it begins to pull away from the bone, then shred. Strain any lard that is not absorbed into the meat and reuse it for other applications (like using it to warm your tortillas).

Similar to American pulled pork, carnitas are best made with large, tough, fatty cuts of the pig. Kelly-Willis prefers pork shanks, but suggests a variety of cuts, including Boston butt and picnic shoulder.

Preserve in salt for house-cured lardo

Lardo, not to be confused with lard, is a different beast entirely (or rather, a different part of the beast). While lard is the smooth, creamy rendered fat from the belly of the pig, lardo is an Italian delicacy made from cured fatback. Lardo can be quite expensive to source as-is, but it’s easy to make yourself if you’re able to purchase a big enough slice of fatback.

“Lardo is made by packing slabs of fat in salt and aromatics and allowing it to sit for weeks to months in a cool dark place,” explained McCullough Kelly-Willis. She suggests using a home vacuum sealer or a non-reactive, air-tight Tupperware container to keep the fatback sealed while it cures.

Making lardo begins with a high-quality sea or kosher salt. Lardo can be cured only in salt, but for additional flavor, Kelly-Willis suggests adding aromatics like peppercorn, bay leaf, rosemary, or fennel seed to the salt mixture before packing the fat. It should then be refrigerated for at least a week, and lardo should be sliced thinly to serve. Kelly-Willis enjoys it as a topping for bruschetta, draped over pizza, or used in place of pancetta in a pasta dish.

Sub for butter in a pie crust recipe

Cold fat and minimal handling are the keys to a flaky pie crust. Typical recipes will call for butter or shortening, though different fats have come in and out of fashion over the years. With shelf-stable convenience food on the rise, the mid-20th century saw shortening as a popular choice in baked goods. But before its invention — and yes, it is an invention, as vegetable oils aren’t naturally solid at room temperature – lard reigned supreme. In fact, according to McCullough Kelly-Willis, “lard is the original shortening and makes a very flaky pie crust or galette dough.”

While butter does have more flavor than lard, lard is typically more affordable and easier to work with — meaning it’s a great choice for those new to pie-making. Lard melts at a higher temperature than butter, making it less susceptible to melting from the heat of your hands. Lard is also pure fat rather than an emulsion like butter. The additional water in butter creates a fluffier texture in the final crust, but it yields less defined edges when crimping.

If you’re working on intricate pastry design, lard is likely the better choice. Additionally, Kelly-Willis noted there are several ways to substitute lard in pie crust. You can swap it entirely for butter, or go with a half-butter, half-lard mixture.

Mix authentic masa dough for tamales

Unless you’re familiar with the Latin American kitchen, tamales seem shrouded in mystery (not just corn husks). Though it’s possible to buy pre-made masa dough, this step is one of the easiest. More than that, as McCullough Kelly-Willis told us, “Lard is a great, authentic way to get supple tortillas and tender tamales.”

Adding a bit of lard to the dough when making tortillas improves their elasticity. In masa for tamales, the fat operates similarly to creamed butter: Its nearly-whipped texture holds air bubbles, even once the liquid is added, yielding a tender, moist, and fluffy tamale. Making masa dough at home begins by beating the lard until it’s fluffy like you would butter for chocolate chip cookies. Be sure to avoid under-whipping the lard, too, as this can yield dense masa dough.

Keep in mind these savory creations are meant to be prepared and enjoyed with a group and many hands are often needed to complete the necessary steps for tamales. There’s shucking and drying out the corn husks, then mixing the masa dough, and making a tasty filling, not to mention assembling each one by hand. With this in mind, Kelly-Willis recommends saving yourself time and energy by using a stand mixer to make the dough.

Swap for butter when frying eggs

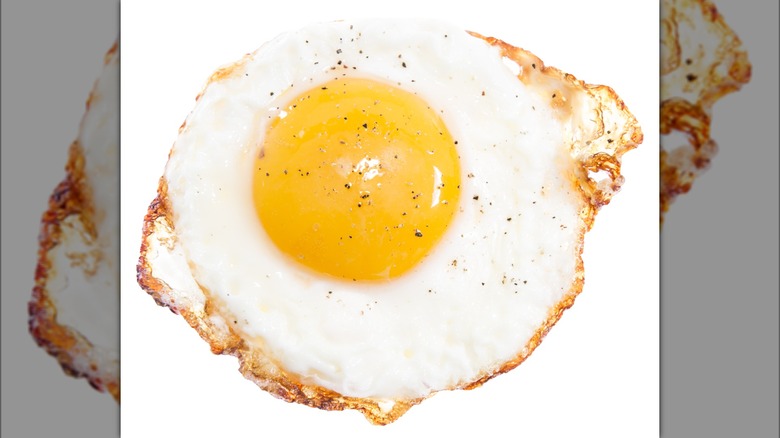

Many have embraced the frilly-edged fried egg, and now, flaccid whites with weepy-looking yolks are a thing of your past. While butter might be your go-to for such textural contrast, lard is a better alternative if you prefer cooking under high heat.

“Lard doesn’t contain sugars and proteins like butter,” McCullough Kelly-Willis said, “making it especially good for achieving a crispy-edged fried egg.” To achieve this result, add a spoonful of lard to your hot pan like you would butter. Because of its high smoke point, you don’t have to worry about the lard burning easily, either.

For additional flavor and texture, try basting your fried egg as it cooks. Gently lift the pan from the burner, leaving it over the heat, and letting the melted lard pool in the side of the pan. Spoon the hot fat over the white and yolk of the egg, similar to how you would baste a pan-seared steak. Basting eggs with melted lard throughout cooking allows the topside of the egg to cook at a similar rate as the underside, and you’ll notice the yolk turning cloudy as the hot fat cooks it from top to bottom. The heat will spread outward, as well, browning the edges through the Maillard reaction.

Confit vegetables or protein with pork fat

“Lard is an excellent fat for confit,” McCullough Kelly-Willis told us, which is “a process of slowly cooking something in fat (usually as a means of preserving it).” By sealing off oxygen exposure, confit foods can last for days, weeks, and even months depending on the food.

The eponymous duck confit utilizes duck fat, but lard works just as well — as does pork instead duck leg. “You can confit pork in lard,” said Kelly-Willis, with several different cuts of pork ideally suited for this cooking method. This process involves first cooking the pork in lard on a simmer, before removing the liquid and finishing it.

Additionally, Kelly-Willis mentioned you can use lard to confit chicken, as well. Of course, while confit is synonymous with meat, vegetables (and even fruits) can also be preserved in this manner. Kelly-Willis suggests firm, flavorful vegetables like shallot, leeks, garlic, or carrots. You can also sub melted lard for olive oil in this simple, flavor-packed tomato confit recipe. To maximize the shelf life of your confit, store food submerged in fat in the fridge.

Make your own cracklins with pork fat

Cracklins are a porky snack that differs from rinds and has a rich history (and an even richer taste). Unlike pork rinds, they’re made from both the skin and the fat of the pig — some cracklin recipes may even leave a small amount of meat on the fat — making them heartier, too. “The key to cracklins is that you need skin and fat,” as McCullough Kelly-Willis explained to Look. “Ideally this should be the skin of the back with some good back fat attached to it,” noting ¼ to ½ inch of fat is a good thickness.

To make cracklins, cut the skin into bite-sized cubes and place it in the base of a cold, heavy-bottomed stock pot or Dutch oven skin-side down. Turn the heat to medium and let the fat slowly render out –- you’re looking for enough fat to coat the bottom of the pan. Once you’ve achieved this, crank the heat to medium-high and, using tongs, continuously flip the cubes as they crisp up.

Kelly-Willis advises patience at this step, as “you don’t want to scorch them!” Once the cubes are ready, transfer them to a paper-towel-lined plate to drain and season with salt right away. Meat rubs, barbecue seasoning, or a pinch of cayenne pepper are welcome here, as well, or any other type of your favored seasoning.

Sear a pork chop

Though multipurpose, at its core? Pork fat is pretty basic. We know fat is essential to cooking well and helps lean foods cook through and evenly -– especially lean proteins. With that in mind, McCullough Kelly-Willis feels “lard will be at home in any recipe you make that includes pork, so next time you make pork chops, use lard to get them going.”

Pork chop is not a singular cut, but a catch-all term describing cuts that come from the loin, or backside, of the pig. Shoulder, rib, loin, and sirloin indicate where the loin was cut, and each will have a slightly different taste and texture depending on the amount of fat, connective tissue, and muscle use (most pigs today are bred to be lean). Rib chops — a familiar-looking eye of lean meat surrounded by a blade of bone at the end — and the common boneless chop is especially lean and benefit from a good bit of fat in the pan before searing.

The added benefit of high-heat cooking in lard is the fat’s high smoke point. Lard’s smoke point is quite high, remember, and you can obtain a beautiful crust with this pork fat according to Kelly-Willis. Just be careful not to overcook lean cuts: The USDA recommends cooking pork between 145 degrees Fahrenheit and 160 degrees Fahrenheit — and a little rosiness in the center is perfectly safe to enjoy.